The best view of New York City may be from a nearly windowless conference room on the 12th floor of a midtown Manhattan office building.

Spread out on 10 folding tables strung together with paper, tape, and sticky notes, the map details every block and subdivision (27,649 homes) below 96th Street and 110th Street on the West Side in Manhattan. It has been.

The map is the work of Bob Nakal, who created it by walking every boulevard and street during the bleak early months of the pandemic.

Updated regularly, parcels are color-coded with highlighters and sticky notes to indicate which ones are for sale (green sticky notes), recently sold (red sticky notes), and owned by the city (pink sticky notes). (highlight) or under construction (green). highlight). An orange highlight means a lot is underutilized and a trade could be made.

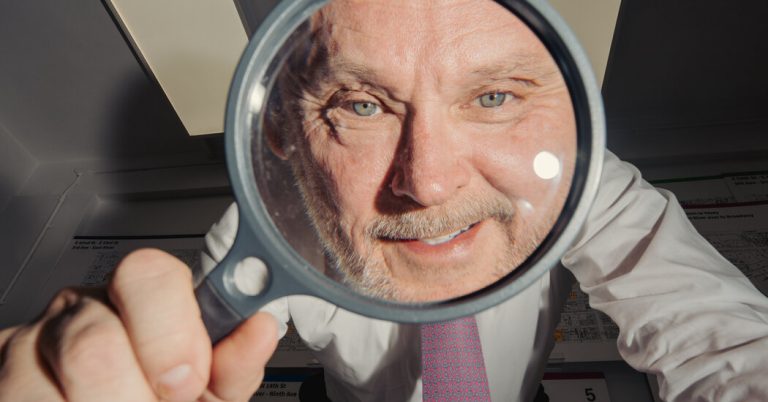

For 40 years, Mr. Nakal has used his obsession with data and creative marketing techniques to earn a rare position in the cutthroat world of New York City real estate. He is widely considered by industry experts to be the top commercial sales broker by number of transactions in the nation's largest commercial market.

“It's not really a real estate business, it's an information business,” Kunakal, 61, said during a recent visit to what he calls the “Map Room,” where his cartographic work is housed.

Since he first began operating in Manhattan in 1984, Mr. Kunakal has sold 2,329 properties, including offices, townhouses, garages, apartments, and warehouses, for a total of $22 billion. His biggest deal was the 2016 sale of several Brooklyn properties owned by Jehovah's Witnesses, including the Watchtower Building in Brooklyn Heights, for nearly $700 million.

He has helped shape New York's skyline, including selling a parking garage on Manhattan's West Side for $238 million in 2014 and the Spiral Office Tower, now one of the city's tallest buildings. became increasingly involved in large-scale transactions.

The sale not only gave Mr. Kunakal enormous wealth, but also access to elected officials.

Cities, especially Manhattan, are becoming increasingly unaffordable for ordinary people, and Kunakal has been stressing this message to lawmakers.

He said his focus on affordable housing is because creating housing is essential to the city's future, but he also said he could benefit from more real estate and development deals. It is also acknowledged that there is a sex.

Over a private lunch in Midtown, he appealed to Gov. Kathy Hochul to do more to encourage the conversion of office buildings to housing. He recently bent Mayor Eric Adams' ear.

He told the mayor that the city owns a lot of properties that are underutilized and have the potential for redevelopment. He specifically called for public housing development, saying it could be preserved while new affordable private housing was built nearby on the same site.

“Look at the vast tracts of land with zero taxes and public housing for a thousand people,” he said. “There is an opportunity to put 10,000 people on that land, use some of that money as taxes, and create tens of thousands of jobs without displacing anyone.””

Some progressive lawmakers and academics blame the affordability crisis on developers and brokers like Kunakal, whose goal is to secure the highest bid for property owners. claims. They argue that as sales prices continue to rise, investors are encouraged to develop projects that can generate greater profits, often resulting in more luxury condominiums.

“A broker's job is to surround themselves with those in power in order to get better deals. So the closer you are to the circles of power and money, the better deals you can broker and the better you can make money.” “We can do that,” Miguel Robles said. Mr. Duran is an associate professor of urbanism at the New School Parsons School of Design.

State Sen. Jabari Brisport, a Democratic Socialist from Brooklyn, said Kunakal should not have a say in building affordable housing.

“He is an example of everything that is wrong with the current housing crisis: that we have allowed housing to be treated as an investment and a financial product rather than a guaranteed right,” Briport said. Told.

“This is a man who got rich on the backs of New Yorkers looking for a place to live,” Bulliport said, adding that Kunakal used his income “to buy political favors from the rich and powerful.” He added that he had arrived.

In response, Kunakal said policies enacted by New York state lawmakers in recent years have significantly slowed new home construction and worsened the housing crisis. It also made developers feel under attack, prompting them to start investing elsewhere, including in the South.

“There is a very big philosophical difference between thinking that housing is a right and thinking that housing is a business,” Kunakal said. “That's way beyond what real estate agents can understand, but I don't think anyone would argue that increasing supply would make rent more affordable for people.”

Kunakal starts each Monday with a legal pad with a handwritten list of dozens of property owners to call. We have a mix of current clients looking to sell, property owners who are not yet ready, and past clients. There are also cold calls.

He makes the calls himself and follows up with emails until the owner gets a call.

In a city crowded with brokers, Kunakal said his name always comes to mind when the phone rings. He emphasized his long history of exclusively representing sellers to potential clients, saying it shows his loyalty.

“Hire me. I'll have your back. I'll be in your corner. I've seen it all, done it all. And I can protect you,” Kunakal said. he said, explaining his pitch. “I can’t say that for other people because they don’t have the same track record.”

His decisive strategy enabled him to win over real estate magnate Harry B. McCraw.

Mr. Nakal cold-called Mr. Mucklow about the one-story retail building for more than two years, eventually calling Mr. Mucklow late one night to avoid the assistant.

This was the beginning of a long-term business relationship that has resulted in more than $350 million in sales to date, including the first property on East 60th Street. Mr. McCraw eventually hired him and sold it for $11.75 million in 2005, about 20 years after his first call. The building was redeveloped into his 42 units of affordable housing.

In Kunakal's office, he is surrounded by printed spreadsheets, bound books detailing transactions and numbers on his computer. He tracks just about everything and rattles off statistics like he's reading the back of a baseball card.

In fact, his oversized business cards resemble baseball cards, with a photo of him holding a baseball glove on the front and annual sales figures on the back.

He also tracks his own performance.

What percentage of calls to former customers ask about another property owner for sale? 9%.

What percentage of prospects hire him after a sales meeting? About 26 percent.

What percentage of prospects who come into the map room for a sales meeting hire him? One hundred percent.

Over the years, he said, his sales numbers have reflected the peaks and troughs of the economy. Real estate sales have declined recently, but not as much as during the savings and loan crisis of the early 1990s.

Kunakal sold just seven properties in the first year of the pandemic, the lowest in 30 years. Sales improved in 2022, but have declined since then due to a sharp and steady decline in large transactions over $10 million across the city.

He said rising interest rates were contributing to a decline in building values, causing owners to continue holding on to their properties out of fear.

Kunakal said most of the owners who are selling now are forced to sell due to reasons such as divorce, disputes or death.

“People don't sell when something puts downward pressure on value,” he says. “The numbers for the fourth quarter are going to be terrible.”

Kunakal splits his weekdays between his office at the Madison Avenue headquarters of JLL, the real estate company where he works, and another building in Midtown where he rents space just for maps.

Kunakal frequently gives tours of the map room, often referring to it during developer calls, and sometimes using a magnifying glass to focus on neighborhoods.

On a recent morning, he guided two executives from the Rockefeller Group, a real estate company, who were looking for housing opportunities in Manhattan.

They scanned the map for possible locations. There's nothing for sale on the Upper West Side, Nakal said. He extended his telescoping pointer over Central Park, showing that there were no green sticky notes in the area.

Pulling the pointer back toward him, he showed the developers several available properties on the Upper East Side and Lower Manhattan. They told him there was nothing that fit right now and it was either too small or too expensive.

Meg Broad, managing director of the Rockefeller Group, one of the developers, said other commercial brokers will also be able to see what's for sale in the city. But no one could match Mr. Nakal's insight and knowledge of trends, geographies and opportunities.

“You want to work with a broker that's on the cutting edge of what's coming to the market,” Broad says. “We want to be one of the first to hear about it.”

Kunakal typically attends events and gatherings around 6 p.m. This is part of his goal to attend 261 networking events a year, one each day he works. He rarely turns down offers to speak at his conference or appear on his podcast, no matter how small the audience.

Over the past year, he has embraced a different kind of networking.He hired a social media manager to teach him how to post on LinkedIn and X, and soon gained many supporters By sharing stories about past deals or making fun of yourself.

He has no plans to slow down or retire anytime soon. “I have no shortage of energy,” he said.